Dear Michael,

Your letter on Christmas Day was a lot to take in, and the holiday season generally has me pretty busy with family and friends. I had to take a few days to think about what you’ve said, before making my reply.

Overall, I’m hearing a lot of dismay, anger and despair in your letter. You’re not alone in these feelings—this cry is going up all over the Internet—but it’s nothing new. This same human sound has echoed throughout the centuries, with every technological advance since the earliest days of the Industrial Revolution.

Any time technology marches forward, it steps on someone’s foot.

Revolution Versus the Resistance

In your letter, you called the reaction of artists in traditional media a “revolution”. But it isn’t a Revolution. It’s a Resistance.

This sweeping reaction we’re seeing to A.I. Image Generators is essentially a labor movement. Artists in traditional media are not agitating for change, they’re agitating to preserve the status quo. They reject the new tech, its makers and its users, because ultimately, they feel that A.I. Image Generation is a threat to their way of life. And while I am generally sympathetic to people fighting for their way of life, I’m slightly less sympathetic in this case—mainly because I feel that they’re fighting for a status quo that has been trying to kill them for years.

The first Luddites were also a Labor Movement. And a Resistance, for what that’s worth. They were reacting in the late 1700’s to a new technology: the power loom.

To put their struggles in context, you need to know a little about the way of life they were fighting for. Throughout the 1600’s and most of the 1700’s, nearly all cloth was produced as a “cottage industry”—spinning and weaving was done in private homes and workshops, by skilled workers. These were primarily men, often organized into professional trade guilds. They used tools like the seated hand loom and the spinning wheel, machines that were developed in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. And they made a decent living churning out thread and fabric which was sold to tailors and merchants.

When the first water-powered looms were introduced in Britain, skilled textile workers saw the machines as a threat. They believed that if this technology were widely adopted, their livelihood would be destroyed.

And they were absolutely right.

Compared to the tech from previous centuries, power looms and spinning jennies allow the production of much more cloth and thread, by much less skilled workers, in much less time. If your goal is to create a simple product and sell it for a profit, there is no way the old cottage industry tech could compete. Water-powered looms and spinning machines are a better answer to the fundamental question of how to make a profit through the manufacture and sale of cloth.

But is “how to make a profit” really the only question that Art is meant to answer?

Any production method that requires fewer workers with less skill is more profitable, even when its outputs have measurably lower quality. And a textile mill takes ownership of tools to make things away from workers, and puts them in the hands of a factory owner. It can also make the years of training the workers have invested in their professional skills irrelevant, at least in the industrial sense. And it breaks the power of their trade guilds, which in some cases had been organized and powerful for centuries.

You end up with a business model where the land owner/factory owner holds all the cards. The workforce has a lot less bargaining power, fewer resources, and they can be paid a lot less money than before. Combine the cost reduction and the centralization of control with the increased speed of production…and there was no way the previous business model could survive.

Does that mean that the art of weaving with the hand loom was immediately and completely lost? That the seated hand loom would never again be economically or politically relevant in the world?

No. Not at all.

The seated hand loom is still used on a daily basis, by people of considerable skill, even now. You can walk into a shop or visit an on-line store and purchase hand-woven fabrics that are made by artisans from all over the planet. It’s safe to say that the old-fashioned hand loom will never again be the way that the CHEAPEST fabric on Earth is made, unless our civilization falls. But people are still using that tool and engaging in the art and craft of hand-weaving. They’re just doing it in different ways, for different reasons, and engaging in a different business model than they were before.

I would argue that the results are often far more beautiful than the cloth made by industrial workers of the past. Hand-woven cloth today transcends the category of “product”. It’s far more purely a work of art.

So the Luddites were not wrong when they thought that a new technology would break their world: it absolutely did. And its impacts were not localized to them; the industrialization of textile production in Britain was inseparable from colonial systems of oppression being brought to bear elsewhere in the world.

The power loom wasn’t just a tool that would disrupt life in England. It helped to subjugate the people of India, who had previously enjoyed world supremacy in both the quality and quantity of their cotton cloth production.

It was no accident that when Gandhi was fighting to throw off British colonial rule in 1920, one of first things he did was call for a boycott of British imports from the textile mills, and a return to everyone in India spinning and weaving their own fabric with old-fashioned spinning wheels and hand looms. He made those old tools into political symbols, and expressions of defiance and identity.

How is all this relevant to the current debate about A.I. Image Generators? Well, I would argue that the lessons to be learned from the Luddites are many.

The first lesson is that Capitalism is not and has never been our friend.

Under capitalism, there is never a time when ANY human being is more important than profit. So we cannot look for salvation from corporations, conglomerates, industries: the business world exists to exploit and discard us, not to take care of us or act in our best interests. That has always been true and it will always be true.

This is why I am somewhat bemused when a random group of creative people suddenly wakes up in 2022 and gets mad because someone made a machine that is capable of making (sorta?) pretty pictures.

Like…damn, creative people. Where have you been?

Your whole neighborhood has been on fire since the 1970's.

And the job losses in creative industries during the Covid crisis rose to the level of a towering inferno. Over 50% of all creative jobs were lost in the USA alone, in 2020—2.7 million jobs overall. The number world-wide sits at nearly 10 million.

And what about the Productivity-Pay Gap? Didn’t ANY of you guys notice that for the last fifty years, ALL working people have been laboring harder and harder for the Man…and getting less and less for their efforts?

Americans are 62.5% more productive today than they were the year I was born—they work more and longer hours, and they put in more effort than ever before. But in that same period of time, their wages have only increased 17.3%. The remaining 45.2% of the time, energy and focus they’re investing in work, in creating profit for others? Is being outright stolen from them, day after day and year after year.

Artists in traditional media want our help to storm Silicon Valley and burn the servers over the invention of a tool for making images from text. If they manage to legislate the current generation of A.I.’s out of existence, I might actually be a bit sad to (temporarily) lose access to the gee-whizzery of text-to-image generation. I would especially miss MidJourney, which I think is pretty cool.

I doubt that they can stop the technological revolution from coming altogether, though. So while I support their efforts to bring their concerns into a court of law, and I have written a couple of essays which I hope will help them understand the enemy well enough to win…part of me feels that the legislation they’re asking for might end up being a tiny Band-Aid on a chest wound the size of a grapefruit.

In my heart of hearts, I know that what’s killing us all is not some relatively simple expert system with dubiously acquired Training Data.

It’s late stage capitalism.

It’s inequality.

They’ve been bad for a long time, and Covid has made them worse.

If creative people die out, I don’t believe it’ll be because of any machine—not even an AI Image Generator. I think it’ll be greed that kills us.

Only a relatively small number of people benefit from our current social, political and economic system. And we all know that those people are not paying their share of taxes, and that they are stealing our wages and our futures—not to mention destroying our planet.

Qui Bono? The Benefits of Disruptive Technology

For me, one of the most striking lines of your letter was this:

“The lack of consent is jarring! We didn’t ask for this. Mostly male engineers think of course they are doing important work. Again mostly male Venture Capitalist do incredible public relations campaigns to hype them! Innovation they plead gleeful with their wallets and pockets open. I cry foul. No, no, this is not how it is supposed to be.”

~ Michael Spencer, “The Artist Revolt vs. A.I. has Begun”

I would agree with you 100% that artists working in traditional media did not ask for this new technology to exist. Nor are they its intended user base, or its beneficiaries.

The cottage industry weavers of England, the users of that hand loom, didn’t ask for the power loom, either. Its development was counter to their best interests and in many ways it undercut their bargaining power in the economy. And while most discussions of textile technology tend to focus on who fought and lost the battle against industrialization, they don’t often focus on who WON.

The quick flippant answer would be to say “wealthy industrialists” were the only victors in that battle, but that is a lie. The truth is that nearly everyone in the modern world benefits from the existence of the power loom and the industrialization of textile production.

Prior to the 1800’s, the average adult man or woman could own only 2-4 sets of clothes. If you walk to your closet right now, and take a good hard look at everything you own…you’ll have to imagine throwing the vast majority of it away. And then having to wear one or two outfits a week, all week, every week, for the rest of your life.

What clothes would you keep? And how much would it affect your life—your professional and social options, your ability to exercise or adapt to changing weather , your ability to express yourself—if all of that affordable, industrial, factory-milled textile material was taken away from you?

And this is just your clothes, of course. We’re not even going to talk about your bedsheets and linens, your towels and rugs, the upholstery on your furniture, every other woven textile that you take for granted in daily life. Thanks to the power loom, most of us can afford to own a lot of textile objects, despite the fact that we are not captains of industry or wealthy aristocrats.

I definitely see A.I. Image Generation as a potentially disruptive, world-breaking technology. Many artists in traditional media see themselves as victims, the losers in this situation—they argue that their way of life will change or even disappear, if the technology is adopted on a large scale.

But I’m not confident that art in older, traditional media will automatically disappear when a new medium emerges. History suggests that this is not how things work: photography didn’t put an end to painting, television didn’t put an end to radio, movies didn’t put an end to live theater, etc.. Hell, even something as overwhelmingly disruptive as the power loom couldn’t kill the hand loom, or kick it permanently off the world stage.

So I think it is at least possible that synthography is not “the death of real human art”, but simply a new medium of art. And I think it’s possible that society as a whole could benefit from a machine that makes beautiful images on command, just as we benefit from the availability of affordable fabric.

The people whose lives could be better won’t ALL be techbro billionaires, any more than the beneficiaries of the power loom are all wealthy industrialists. The modern world as we know it, and many artistic fields like fashion and clothing design, interior design, costume design, cosplay, quilting, etc. simply could never have come to exist in their current relatively democratic form without the affordable, easily-accessible industrial fabrics that emerge from the power loom and its mechanical descendants.

Someday we might be surrounded by a world of amazing things that are made possible by AI tools. At the end of the day, I’m more curious to see that world than I am afraid of the turbulence that comes with its advent.

Disruptive Technology and Its Unseen Ends

There are many more things I could say about spinning, weaving and the value of textile art in our daily lives and culture. But right now, I have to point out the elephant in the room: the effects of the power loom on human society were not limited to textiles.

I am currently sitting at my kitchen table writing this letter on a laptop computer—and it is arguably the case that modern computer technology would not exist, and certainly would not exist in its current form, if it were not for the power loom.

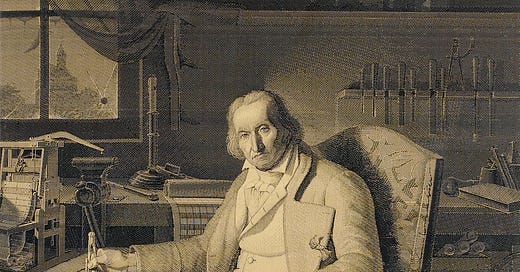

You see, the first programmers were loom programmers. This portrait of French inventor J.M. Jacquard was woven in silk, using a Jacquard loom which was programmed with over 24,000 punch cards.

Charles Babbage developed the first Analytical Engine in 1840, inspired in part by the operation of the Jacquard Machine. He owned a copy of the silk portrait above and would challenge visitors to guess how it was made—they usually failed.

The first computer programmer, Ada Lovelace (a.k.a. Ada Augusta Byron, daughter of the famous poet) freely acknowledged that the Analytical Engine owed its existence to its technological predecessor:

“—the Analytical Engine weaves algebraical patterns just as the Jacquard-loom weaves flowers and leaves.” ~ Ada Lovelace

In short…we can never see all the ends of a disruptive technology. We live in a world where the Luddites lost. And because they lost, I get to own more than three shirts and I’m able to write you this letter about machines on a machine that would not exist if they had won.

I can only speak for myself, here, but…I’m not so in love with the world as it currently exists that I cannot bear to see it change. If this tech could break the world…maybe the world to come will be better? Or at least interesting.

A Few Last Words

You ended your letter by asking whether there was any comfort or peace to be had, in this turbulent world of AI Proliferation. I want to end my reply by offering at least two crumbs of hope.

One, visual artists who feel that they have been incorporated into the Training Data of an AI Image Generator without their consent DO have a legal case to make. And win or lose, I believe that all creative people should support them in making their case.

The incorporation of copyrighted images into Training Data without consent is not just a “visual arts” issue. It is a human rights issue. The same is true of any data set scraped without attribution or consent from the world wide web and used to build any AI…but particularly one which is likely to disrupt the economic activities of working people.

Why is this Training Data issue everyone’s problem? Because all human beings, whether they are in creative professions are not, need to recognize that our participation in the Internet over the last thirty+ years has created a massive planet-wide digital commons. AND IT BELONGS TO US.

The value of the web is something we have collectively created. It is a woven tapestry of our time and energy, our hopes and dreams, our art and poetry, our songs and jokes, our thoughts and feelings, more than thirty years wide and still growing every day.

This symphony of human communication that we have all collectively performed does not belong to the Big 5. It does not belong to Elon Musk, or Jeff Bezos, or any other techbro billionaire dickloaf. It does not belong to the Russian Mafia, or the Chinese government, or the world-wide fascist uprising. And it certainly doesn’t belong to the developers of AI’s and their investors, either.

It belongs to US. And we need to fight for every inch of it.

Two, we really do need to decide, collectively, how we are going to bring the Powers That Be to heel. And we need to start showing up for each other in ways that really count.

The only reason automation in ANY industry is scary, in my opinion, is that most human beings on this planet are living on increasingly narrow margins. If we lose our jobs, most of us are only weeks away from life-destroying economic disaster. And we clearly cannot trust our institutions (governments, industries, corporations) to act in ethical ways, or in the interests of humankind.

That means we have to flex our human power. And it will take more than social media manifestos to fix what’s wrong with this world.

We have to vote. We have to organize. We have to throw our economic weight behind causes that matter and candidates that promise change; and when we don’t have money to throw at a problem, sweat equity will have to do.

If you’re really worried about human artists—do what I do. Hire an artist. Pay an artist.

And if you’re worried about AI’s violating the rights of visual artists, contribute to the GoFundMe of the Concept Art Association. I pitched in myself, in point of fact; I decided to give them the same $600 that a professional account with MidJourney costs. Since it is the only AI I have yet paid money to use, I figured that it was only fair to give an equal amount of money to the human beings who want to regulate the industry, and give them a fighting chance.

I hope you’re having a happy holiday season, Stephen. And I look forward to hearing from you again.

Cheerfully yours,

Arinn Dembo