When I was a child, my grandparents lived in a House of Wonders.

The house stood on Spruce Street, within walking distance of the University of Pennsylvania. It was one of many along that row, ground structures built by prosperous families who had made their fortunes in the decades following the American Civil War. This particular house had been built by an English sea captain, an impressive brick structure of brick and hardwood and glass with a spacious front portico and back garden; like all the other houses along that street the building had been subdivided in the 20th century, but even owning half of such a house was impressive.

The interior of the House of Wonders was three floors, plus an enormous open basement and a lofty attic. The main floor opened from the front door into a large open sitting room that may have been half of a small ballroom when the house was first built. As you moved on there was a large dining room with a table that would easily accommodate twelve to eighteen people as well as china cabinets and side tables. A narrow pantry separated the dining room from the spacious kitchen, which had a smaller table for informal meals and food prep. Through the kitchen windows you could look into the back garden, and there was a rear entrance there that led down into the shade of a towering mulberry tree.

All of the ceilings of that lower floor were very high, architecture from a time before air conditioning, when people knew how to beat the heat of the mid-Atlantic summers by giving it a place to go. I remember how they seemed to tower over me as a child, and how the high mantle of the fireplace in the sitting room was out of my reach. I had to climb up onto a chair to see the sculptures lined up on that mantle shelf—smooth curving forms of animals carved from a golden-brown wood, black masks with strange geometric features that were hypnotic in their grave, unsmiling serenity.

This was my first encounter with African Art.

I can’t say how old I was when I first encountered those sacred things. My clearest memories of them date from when I was six and seven, old enough to be given free reign to wander the House of Wonders and touch all of its magical things without too much direct supervision. I believe the last time I spent any significant time in the House was when I was fifteen or sixteen, and spending the last significant time I would have with my grandfather before his decline and death in the 1990’s.

One of the most memorable pieces was a wooden gazelle carving. My grandparents would have picked it up abroad while my grandfather was in the US Foreign Service, perhaps some time during the 1950’s or early 1960’s. I believe my grandmother was probably the art collector in the family, but at this late date I cannot be certain. My grandfather had great respect for art as well, and often made a point of taking me to the Philadelphia Museum of Art as a child—not only to play in the fountains with the other children of the city, but to wander the halls and feast my eyes on its collections of armor and furniture, or to see some special exhibit.

It was a beautiful piece, very similar to the one in the photo above. This particular gazelle was carved in Tanganyika before 1963, an area which is now part of modern Tanzania—it was a gift to President John F. Kennedy from Julius K. Nyerere, the Prime Minister of Tanganyika, during a state visit.

The gazelle carvings owned by my grandparents may have been a few inches smaller than this, but they were every bit as fine. They had the same smooth curves and polished grain. The wood of such vintage carvings is probably muhuhu, African sandalwood, still one of the most highly prized woods for use by traditional woodcarvers in east Africa today, but also facing extinction due to the demand of foreign markets for other uses of the wood.

I’m not sure that such carvings are often made today. After seventy years the availability of the wood and the styles of modern woodcarvers may have changed too much. But my point is not just to dote upon this object as an object, precious treasure though it might be. The golden brown gazelles, the black masks and statues, the zebra skin drum in the House of Wonders were not just treasures, they were artifacts—physical evidence of a world and a culture that was not my own.

The feeling I had looking at them as a child was not just a desire to touch them or to own them but to understand them, to know more. It was awe and curiosity and longing. And much as I love science fiction, it was probably as close as I will ever come to confronting an alien intelligence in real life.

This sculpture was a work of genius and love. It was carved from a tree that grew in exotic soil, still perfumed with the tree’s fragrant resin. A sure and skilled hand had carved and polished this wood in a visual language that my own people did not speak, to capture a moment of living grace—a vision of an animal from another world.

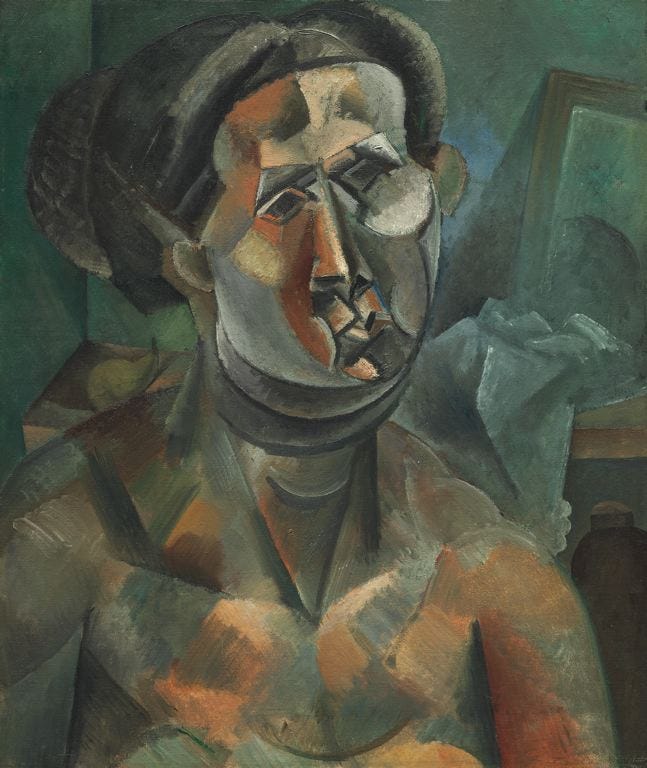

I was not the first person to have that shock of awe in the face of African Art. Picasso and many of his contemporaries had the same response, when they first encountered African art in the early 20th century. It took Picasso three years to process his response, years when he struggled to understand it through imitation—the years between 1906 and 1909 are still often known as his “African” or “Black Period”. More to the point, those were the formative years of a painting style that would eventually emerge from the collision of Black and White art—Cubism.

Of course I am no Picasso; I was never destined to become a painter. But that spark of awe and longing to understand was probably similar. Any person who can recognize great art and open their eyes and minds to it could experience the same thing. African Art is a concrete, physical manifestation of Black minds and Black hearts and Black souls… and the beauty that lives there.

As such, it will forever have my respect.

Sculpture of a Male Gazelle, John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum